No discussion of African-American history in Osceola County is complete without recalling Kissimmee High School.

Many do not know that, until 1968, Osceola High School had a companion in the city of Kissimmee. Kissimmee High was the all-black school for the entire county, meaning that students, starting in first grade, countywide— Kissimmee, St. Cloud, Narcoossee and even Holopaw—attended the school, located near the intersection of Cypress Street and Central Avenue.

Until sometime in the 1940s, the school only taught through 10th grade, meaning black students had to go elsewhere—many went to schools in Orlando or Eatonville, an African-American community near Maitland—to graduate.

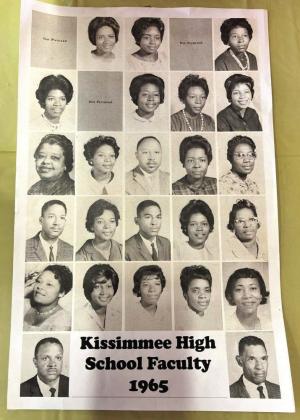

William Edward Patterson became principal of Kissimmee High in 1946, around the time it began serving students through 12th grade, and held that position until the school’s closing in 1968, following integration.

After passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, previously segregated schools were mandated to integrate. In Kissimmee, Kissimmee High would be joined in with the previously allwhite Osceola High for the 1966-1967 school year. Hoping to get an early start on the process, the school district asked for volunteers from Kissimmee High to be the first to integrate Osceola High starting in the fall of 1965.

Last year, Osceola High honored the memory of Charles Martin, the only senior who volunteered and the only African-American member of OHS’ Class of 1966.

Members of the OHS Class of 1967—the first to come from Kissimmee High to integrate Osceola—like Diane McCullough Tisdale, Virdess Brown Word and Lawrence Howard, all knew Martin, by his nickname “Charlie Boy”.

While the integration could have been filled with racially-motivated angst, all three said theirs was a good experience.

“I didn’t experience any problems. Personally, I would have liked to stayed at Kissimmee High School,” Howard said. “Students had a relationship with teachers, who would help students one-on-one if they needed help. Everyone knew everyone—students, parents, teachers—it was like one big family; a school full of love.”

Tisdale moved from the Jacksonville area to Kissimmee to live with her grandmother, who as one of the area’s first black nurses was able to take care of her health conditions. Tisdale attended Kissimmee High School for five years, and when it came time to move over to Osceola High for her senior year, she wanted to get familiar with it.

“I took an accounting class over the summer, to get comfortable with the school,” she said. “I didn’t feel like it was any different (than KHS).”

By the following fall, she said the Kissimmee transfers were welcomed, and OHS students even made a point to introduce themselves.

“It really became one Osceola High community,” Tisdale said. “I don’t recall any of us having problems with any of the teachers. If the community had issues, we didn’t know anything about it.”

Word, a classmate of Howard and Tisdale, was born and raised in Kissimmee before eventually moving to Georgia like Howard. Word did not go to Osceola High, choosing to attend her senior year at Orlando’s Jones High School, but said many of her best memories came from Kissimmee High School.

“I was the baby of seven, and all of my siblings went to Kissimmee High School. By the time I got there all the teachers knew me,” she said with a laugh.

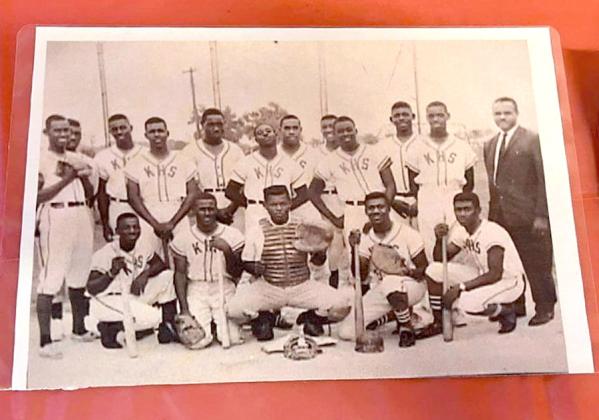

In her time at Kissimmee High, she played on the school’s girls basketball team.

“The county wouldn’t let the school have a gym, so we played on an outdoor concrete court with a wooden fence around it, and when we played there was always a crowd. Those were some of the best times of my life. My only regret was that we would get used books, that other students had written in and such.”

Howard noted that, when Kissimmee High closed, none of the black teachers there were offered other local high school positions.

“They had to take junior high positions if they wanted to stay in Osceola County. And we had some of the greatest minds for teaching,” he recalled.

One all three mentioned was science teacher Evan McKissick— “No other teacher could compare to him,” Howard said—who also served as a photographer and timekeeper for the local black community.

“When we transferred to Osceola, he kept up with the black community of Kissimmee High,” Tisdale said. “He had all these pictures. He could have opened a Black history museum all by himself.”

The only time the KHS transfers felt uncomfortable, Howard said, was during the senior prom at the Tupperware center. It set the stage for the KHS classmates to get together annually, which they do to this day, although COVID-19 turned them into online remote reunions they last few years.

“I’m praying we get back to face-to-face reunions soon,” Word said. “They are such a highlight every year.”

“When we walked into the Prom, we entered to Rebel flags and the like,” Howard said. “We realized we couldn’t stay, so we left. That’s the reason we celebrate our Kissimmee High School class reunion every year.

“We still try to get together and enjoy each other’s company while we’re still here, to laugh and talk about old Kissimmee High.”